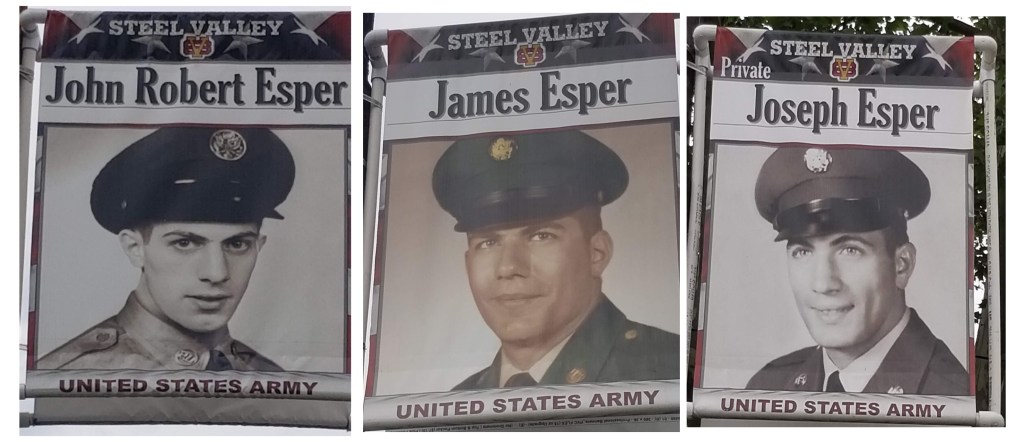

We have come upon Memorial Day 2020 in the age of corona. Its the traditional first day of summer, and across the country, people are in an argument as to whether or not they should be allowed to go to the shore and get their nails done. We, as a country, have long forgotten the exact reason we celebrate this holiday, other than to parade old men holding flags down our main streets as a form of honor and reverence; followed by the mass consumption of burnt meat. And on the Tuesday following we return to subjecting these heroes to the indignities of old age, to live in their own memories alone and away from us. What did they leave behind for us to hold onto? What was flying above them as they hit the beaches of Normandy, Anzio and Iwo Jima? It wasn’t a flag I can assure you. It was an idea that all of us bear a responsibility to each other to participate in the idea of a democracy to achieve the idea of freedom. And ideas, being non-corporeal and mutable, have the most difficult time taking hold if they aren’t universally acknowledged and practiced.

Soldiers participate with the highest risk and each individual service carries with it the most potent form of this idea: a human being risking harm for an ideal. There’s no second guessing the nature of the participation: if you’re in a uniform, it carries mortal risk. When we vote, we participate as well, and perhaps the voting polls would swell if there was something more physically tangible at risk if we neglected to do so. But there isn’t which is why so many of us rationalize our neglect of this exercise.

The one form of participatory democracy that gets routinely ignored is jury duty. It is derided by many as “already rigged”, “boring”, “a waste of my time” and in terms of avoidance ranks lower than voting only because you are legally mandated to answer the summons of duty. But if your local community did not send out a summons, no one would serve and the jury box would be routinely empty. While I did not choose to serve in the armed forces, and while I strive to make sure my vote is counted, the biggest civics lesson of my adult life was learned sitting in the jury box. I served on 2 separate juries, one criminal, one civil; one in Brooklyn and one in Los Angeles. And in each case, the lesson administered by the judges, was the same, simple and supremely valuable: be sure to listen and be careful how you speak.

When charging the jury with the case, each judge (a woman in Brooklyn, a man in Los Angeles) gave the us the same instructions. After the first time I realized I’d heard parts of it in countless plays, TV shows and movies over the years, truncated to fit the time constraints of drama. After the second time, I realized how critical it was not just in the deliberation room but to every interaction we have with each other.

In a manner of words, as I paraphrase, each judge instructed us similarly: “there is a reason we don’t allow jurors to take notes: the individual perception you have of the proceedings in court is what makes the strongest collective agreement to the outcome of justice. Each of you heard the same words but perceived it differently according to your own backgrounds and biases. So in acknowledging our differences, it becomes critical that you intently listen to your fellow jurors and consider with gravity what each has to say. The words you form to express your perceptions made here have meaning and consequences in the deliberation room. Therefore, do not leave this jury box with your mind made up, for if you speak that decision too early in the deliberation, and new evidence is put before you in the form of someone else’s recollection of the same events, you will, because of pride, be reluctant to change your mind, fearing that you will have lost credibilty. And then justice will not have been served. Truth is not secondary here, but truth is dependent on justice being first, and justice is best served when people of different perceptions come together in full agreement.”

I don’t think I’ve come across wiser words ever spoken to me. When I put those words together in the everyday practice of life, I can think of no more beneficial way to interact with other people; no better form of communication skill, no more constant form of persuasion, no better way to honor the sacrifice of those we raise a flag to once a year. Everything from our personal relationships to our business affairs to our participation in various govenmental forms depends on carrying out the wisdom of these words.

But many of us never get the chance to know this wisdom first hand: not just the hearing of the words, but the opportunity (and duty) to put them immediately into practice. It takes patience, empathy, humility and a lot of self-control, qualities that have slowly evaporated in the public life we share with each other. If we don’t know this wisdom then we can’t claim full participation in this idea we all share. Every loud protestation of our “rights” in the public arena will ring hollow inside our heads, causing a cognitive dissonance that keeps us agitated. And when that agitation finds its normalcy in you, we become ripe for the plucking from any grifter that promises to take that agitation away.

Memorial Day. Full of more honor and lessons that lie deeper than just waving a flag.

Enjoy your hot dogs. Wear a mask in public. And don’t scream about your rights being taken away if you’re not protecting someone else’s.